In the complex landscape of nutritional science, zinc has long been lauded as an essential mineral, pivotal for immune function, enzymatic reactions, and cellular metabolism. Its popularity as a dietary supplement and its role in evaluating nutritional sufficiency often lead to a focus on its density within foods and supplements. However, equating zinc density directly with overall nutritional value oversimplifies the multifaceted nature of diet quality. Recent research indicates that relying solely on zinc density as an indicator of nutritional adequacy might be misleading, necessitating a nuanced exploration of how zinc fits into the broader nutritional matrix.

Zinc Density Versus Nutritional Value: Underlying Paradigms

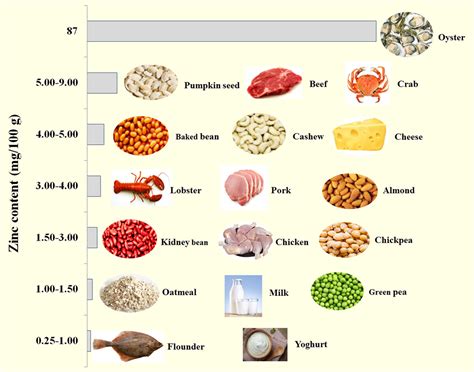

At first glance, zinc density—commonly measured in milligrams per 100 grams or per serving—serves as a convenient quantitative metric for assessing how much zinc a particular food provides. This measure is particularly useful for dietary planning, especially in contexts where zinc deficiency is prevalent or in clinical nutritional support. Countries with a high incidence of zinc deficiency often promote foods rich in zinc, such as seafood, legumes, and fortified cereals, partly based on their zinc density metrics.

Nevertheless, nutritional value encompasses a broad spectrum of nutrients, including macronutrients, micronutrients, bioavailability, and the presence of anti-nutrients or phytates that inhibit mineral absorption. Therefore, a food item with high zinc density might simultaneously harbor compounds that impede zinc bioavailability or could lack other vital nutrients necessary for balanced health. This complexity underscores the importance of a holistic approach rather than a narrow focus on zinc density alone.

Limitations of Zinc Density as a Standalone Indicator

One primary challenge with using zinc density as an exclusive marker lies in the bioavailability of zinc. For instance, plant-based foods like grains and legumes often contain phytates—organic compounds that chelate zinc ions—reducing actual absorption rates. A food with high zinc content but high phytate levels offers less bioavailable zinc compared to a food with less zinc but higher bioavailability.

Another consideration is the presence of other micronutrients or compounds that influence zinc absorption and utilization. For example, calcium and iron—while essential—can compete with zinc for absorption pathways in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, a high-zinc food consumed alongside calcium-rich dairy might not translate into elevated zinc status in the body, regardless of its zinc density.

Furthermore, nutritional value extends beyond micronutrients to include fiber, antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and phytochemicals. Foods with high zinc density may lack these components or may even be detrimental if they contain antinutrients or allergens. Conversely, nutrient-dense foods like liver or shellfish offer a rich array of nutrients beyond zinc, contributing to overall health in way that zinc density alone cannot capture.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Zinc Content in Foods | Oysters: approximately 74 mg per 100g; Legumes: 3-5 mg per 100g; Beef: about 4.8 mg per 100g |

| Bioavailability Factors | Phytate content can reduce zinc absorption by up to 50%; Animal sources generally have higher bioavailability than plant sources |

| Other Nutrients | Liver: high in vitamin A, iron, copper, and zinc; Nuts: rich in healthy fats, vitamin E, selenium |

Contrasting Perspectives: Emphasizing Zinc Density versus a Holistic Nutritional Approach

Proponents of using zinc density as a key nutritional metric argue that in resource-limited settings, it offers a practical, quantifiable means to identify foods likely to combat zinc deficiency. For example, nutritional surveys in developing countries often prioritize zinc-rich foods, like shellfish or fortified grains, because their high zinc density correlates with improved immune function and growth outcomes in undernourished populations. Moreover, setting zinc density thresholds can aid public health policies by fostering food fortification programs or dietary recommendations aimed at preventing deficiency.

Nonetheless, critics highlight that a narrow focus on zinc alone may inadvertently promote consumption of foods that are not nutritionally balanced or are high in antinutrients. They argue that emphasis should be placed on dietary patterns, overall nutrient density, and bioavailability. For instance, promoting plant-based foods with moderate zinc content but high bioavailability coupled with a variety of other nutrients aligns better with sustainable, health-promoting diets. The Mediterranean diet exemplifies how nutrient synergy—a diverse intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, fish, and whole grains—far exceeds the benefit of high zinc density alone.

Real-World Applications and Practical Implications

In clinical nutrition, emphasis on zinc density can guide supplementation, especially in cases of diagnosed deficiency. However, practitioners also recognize that supplementing with zinc alone may not be sufficient. Clinical trials have demonstrated that combining zinc supplementation with nutritional improvements results in more sustainable health gains, emphasizing the importance of dietary diversity.

In public health strategies, zinc fortification of staple foods like wheat flour or rice has been effective in reducing deficiency across populations. Yet, these interventions are complemented by education on dietary diversity to maximize nutrient synergy and bioavailability—highlighting the shortcomings of a zinc-centric paradigm.

Additionally, emerging research explores the role of food matrices and digestive dynamics, revealing that the physical and chemical structures of foods influence zinc absorption in ways that raw zinc density does not reveal. For example, fermented foods or sprouted grains can alter phytate levels, increasing bioavailability, and exemplify how processing techniques modify the practical zinc contribution of foods.

Key Points

- High zinc density alone does not guarantee overall nutritional adequacy due to bioavailability and nutrient interactions.

- Holistic dietary assessments incorporate multiple nutrients, food matrices, and bioactive compounds for comprehensive guidance.

- Bioavailability modifiers, such as food processing and dietary context, are crucial for translating zinc content into physiological benefit.

- Practical health interventions benefit from integrating zinc density metrics with dietary diversity and nutrient synergy principles.

- Future research should emphasize food matrix effects and personalized nutrition to optimize zinc utilization within diets.

The Bottom Line: A Balanced Perspective on Zinc Density and Dietary Quality

Reflecting on these competing viewpoints, it becomes evident that while zinc density is an important piece of the nutritional puzzle, it should not be the sole criterion for evaluating diet quality. Instead, a multidimensional approach—considering bioavailability, nutrient interactions, food processing, and overall dietary patterns—can better serve public health goals and individual nutritional needs.

Recognizing that different foods contribute to health in unique ways and that nutrients rarely act in isolation helps avoid reductive strategies that rely solely on quantitative measures. As nutritional science advances, integrating innovative techniques such as metabolomics and personalized nutrition can further refine how we interpret zinc’s role within diverse dietary contexts, ultimately fostering more effective, sustainable, and holistic nutritional policies.

In sum, zinc density provides valuable insights but must be contextualized within a broader framework—an approach that captures the complexity and richness of human diets, rather than reducing them to single-nutrient metrics.

Why is zinc bioavailability important when assessing its dietary contribution?

+Zinc bioavailability determines how much zinc from food is actually absorbed and utilized by the body. High zinc content in foods does not guarantee effective absorption—foods rich in phytates or high calcium can inhibit zinc uptake. Therefore, understanding bioavailability is essential to accurately assess zinc’s contribution to nutritional status.

Can foods with low zinc density still support adequate zinc nutrition?

+Yes. Foods with lower zinc density can supply sufficient zinc if they have high bioavailability, good absorption conditions, and are part of diverse diets rich in complementary nutrients. Overall dietary patterns matter more than zinc content alone in ensuring adequate intake.

How do food processing techniques influence zinc bioavailability?

+Processing methods such as soaking, fermenting, or sprouting can reduce phytate levels in plant foods, thereby increasing zinc bioavailability. This highlights the importance of considering food preparation techniques when evaluating the nutritional contributions of zinc-rich foods.

What role do dietary patterns play in zinc nutrition?

+Dietary patterns that include a variety of nutrient-dense foods—such as seafood, nuts, legumes, and vegetables—support not only zinc intake but also optimize nutrient synergy, absorption, and overall health. Focusing purely on zinc density ignores these broader dietary benefits.

Should public health policies prioritize zinc density in food fortification?

+While zinc fortification can effectively combat deficiency, policies should also promote dietary diversity and consider bioavailability considerations to maximize health benefits. Combining fortification with nutrition education yields better and more sustainable outcomes.